Sejarah Okultisme Jawa (The Occult History Of Java)

Pemahaman tentang Okultisme

Okultisme adalah kepercayaan terhadap hal-hal supranatural seperti ilmu sihir. Kata "okultisme" merupakan terjemahan dari bahasa Inggris, occultism. Kata dasarnya, occult, berasal dari bahasa Latin occultus ('rahasia') dan occulere ('tersembunyi'), yang merujuk kepada 'pengetahuan yang rahasia dan tersembunyi' atau sering disalah-artikan oleh masyarakat umum sebagai 'pengetahuan supranatural'.

Okultisme yang sebenarnya adalah bukanlah hanya sihir dan lebih tepatnya bukanlah supranatural, karena pada dasarnya okultisme adalah ilmu yang alami. Okultisme adalah ilmu yang mempelajari pengetahuan tersembunyi yang terdapat dalam alam semesta, pada diri dan lingkungan kita. Tujuan akhirnya bagi praktisi okultisme adalah pemahaman dan pengertian yang sebenarnya tentang diri sendiri yang lebih tinggi yang kemudian akan menghasilkan pencerahan dan kebijaksanaan yang akhirnya akan mendekatkan diri pada sang pencipta.

Okultisme yang sebenarnya adalah bukanlah hanya sihir dan lebih tepatnya bukanlah supranatural, karena pada dasarnya okultisme adalah ilmu yang alami. Okultisme adalah ilmu yang mempelajari pengetahuan tersembunyi yang terdapat dalam alam semesta, pada diri dan lingkungan kita. Tujuan akhirnya bagi praktisi okultisme adalah pemahaman dan pengertian yang sebenarnya tentang diri sendiri yang lebih tinggi yang kemudian akan menghasilkan pencerahan dan kebijaksanaan yang akhirnya akan mendekatkan diri pada sang pencipta.

Lebihlah mudah untuk mempelajari trik, ilusi, ilmu, dan metode yang menggunakan teknik memanipulasi energi yang ada pada alam, berbagai pengaruh yang bervibrasi rendah, kekuatan yang ada pada emosi manusia, energi yang kasat mata, yang dipahami, dipelajari dan kemudian dimanipulasi. Tetapi hal ini merupakan ilmu hitam (black magic) yang motivasinya sering berdasarkan kepentingan sang individu yang menyalahgunakan ilmu ini.

Okultisme seperti berbagai ilmu pengetahuan lainnya merupakan pengetahuan yang bersifat netral yang tidak memihak. Hanya motivasi sang praktisilah yang akan menentukan hasil akhir dari praktik dari pengetahuan ini.

Kualitas okultisme adalah properti yang tidak memiliki penjelasan yang rasional. Dalam Abad Pertengahan, magnetisme kadang-kadang disebut kualitas okultisme.

Sezaman Newton sangat dikritik teorinya bahwa gravitasi dihasilkan melalui "tindakan yang kelewatan" sebagai okult.

Dalam zaman prasejarah pulau-pulau ini masih merupakan bagian dari benua Asia. Pada saat ini Laut Jawa hanya 200 ft. Dalam, dan kelanjutan dari saluran dipotong oleh sungai dari Sumatera dan Kalimantan masih dapat ditelusuri di bagian bawah lembar relatif dangkal air. Bahkan sampai dengan tahun 915 Masehi pulau Jawa dan Sumatera adalah salah satu, dan itu adalah letusan Krakatau pada tahun itu yang pecah antara keduanya dan menciptakan Selat Sunda. Wabah pada skala tertentu karena hal ini sering hancur seluruh kerajaan, dan memiliki pengaruh serius pada sejarah negara.

piring III

piring III

Several curious things may be noted in connection with these statues. They are not in the least the traditional half-Mongolian Buddha figures; the faces are clearly Aryan, and also quite individual—indeed, they are supposed to be portraits. The Lord Buddha is seated as a European and not as an Asiatic, and the others are at least halfway between the two postures. The edge of the Lord’s robe is conventionally indicated by a line, yet it does not seem to conceal the rest of the body. Both of the other statues are much more ornately dressed, wearing necklaces, armlets, wristbands, anklets and tiaras; and it is remarkable that these ornaments are far more Brahmanical than Buddhistic in character.

Okultisme adalah kepercayaan terhadap hal-hal supranatural seperti ilmu sihir. Kata "okultisme" merupakan terjemahan dari bahasa Inggris, occultism. Kata dasarnya, occult, berasal dari bahasa Latin occultus ('rahasia') dan occulere ('tersembunyi'), yang merujuk kepada 'pengetahuan yang rahasia dan tersembunyi' atau sering disalah-artikan oleh masyarakat umum sebagai 'pengetahuan supranatural'.

Lebihlah mudah untuk mempelajari trik, ilusi, ilmu, dan metode yang menggunakan teknik memanipulasi energi yang ada pada alam, berbagai pengaruh yang bervibrasi rendah, kekuatan yang ada pada emosi manusia, energi yang kasat mata, yang dipahami, dipelajari dan kemudian dimanipulasi. Tetapi hal ini merupakan ilmu hitam (black magic) yang motivasinya sering berdasarkan kepentingan sang individu yang menyalahgunakan ilmu ini.

Okultisme seperti berbagai ilmu pengetahuan lainnya merupakan pengetahuan yang bersifat netral yang tidak memihak. Hanya motivasi sang praktisilah yang akan menentukan hasil akhir dari praktik dari pengetahuan ini.

Kualitas okultisme adalah properti yang tidak memiliki penjelasan yang rasional. Dalam Abad Pertengahan, magnetisme kadang-kadang disebut kualitas okultisme.

Sezaman Newton sangat dikritik teorinya bahwa gravitasi dihasilkan melalui "tindakan yang kelewatan" sebagai okult.

Sejarah Okultisme Jawa (The Occult History Of Java)

The Occult History Of Java

Sejarah

sejarah awal Java tampaknya terbungkus dalam misteri. Dari membaca sebagian besar buku yang ditulis dalam bahasa Inggris tentang subjek yang akan menyimpulkan bahwa pulau ini sepenuhnya diketahui oleh seluruh dunia sampai dikunjungi oleh peziarah Cina Fa Hien pada tahun 412 Α.D .; dan bahkan setelah itu ada pada interval kesenjangan beberapa abad yang tampaknya saat ini tidak mungkin untuk mengisi dengan cara biasa.

Sisa reruntuhan berlimpah, tapi hampir tidak ada dari mereka yang berusia lebih dari 1200 tahun, dan sangat sedikit catatan atau prasasti telah diawetkan. Ada Tradisi tertentu yang telah diturunkan antara keluarga bangsawan Jawa; tapi bahkan mereka menjadi jelas apokrif seperti yang kita mengikuti mereka kembali ke awal era Kristen, dan lebih dari itu mereka adalah legenda yang luar biasa belaka. Mungkin itu tidak perlu mengejutkan kita, karena setelah semua kita bisa menelusuri sejarah Inggris lagi!

Dengan memanggil bantuan clairvoyance kita tentu saja dapat membawa penyelidikan kami kembali tanpa batas waktu, tetapi untuk tujuan kita sekarang akan cukup untuk mencoba untuk memeriksa kondisi yang ada di negara tempat sekitar 2000 SM Jauh sebelum itu pulau-pulau ini pernah menjadi koloni Atlantis, tapi ketika Atlantis bubar mereka menjadi sebuah negara terpisah, yang melewati banyak perubahan-perubahan sebagai usia bergulir. Ini bagian dari dunia telah lama menjadi wilayah aktivitas vulkanik yang kuat, yang belum bahkan sekarang sepenuhnya mati, seperti yang disaksikan oleh letusan besar Krakatau pada tahun 1883, yang menewaskan 35.000 orang, dan menyebabkan 50-ft. gelombang pasang yang berwisata sejauh Cape Horn, 7818 mil jauhnya, dan bahkan mempengaruhi tingkat Thames sungai di London, selain membuang begitu besar volume debu yang naik ke ketinggian dua ratus mil dan memberikan seluruh dunia dengan matahari terbenam fenomenal indah selama dua tahun setelahnya.

Dalam zaman prasejarah pulau-pulau ini masih merupakan bagian dari benua Asia. Pada saat ini Laut Jawa hanya 200 ft. Dalam, dan kelanjutan dari saluran dipotong oleh sungai dari Sumatera dan Kalimantan masih dapat ditelusuri di bagian bawah lembar relatif dangkal air. Bahkan sampai dengan tahun 915 Masehi pulau Jawa dan Sumatera adalah salah satu, dan itu adalah letusan Krakatau pada tahun itu yang pecah antara keduanya dan menciptakan Selat Sunda. Wabah pada skala tertentu karena hal ini sering hancur seluruh kerajaan, dan memiliki pengaruh serius pada sejarah negara.

Black Magic dari Atlantis

Para kolonis dari Atlantis pada hari-hari awal telah membawa bersama mereka agama gelap dan jahat negara mereka, dan sebagai waktu bergulir, cengkeramannya pada orang menjadi semakin kuat dan lebih merusak. Hal ini didasarkan sepenuhnya pada rasa takut, seperti semua agama ini suram; mereka menyembah kejam dan keji dewa, yang diperlukan pendamaian konstan dengan pengorbanan manusia, dan mereka tinggal pernah di bawah bayang-bayang tirani mengerikan yang ada jalan keluar mungkin.

Mereka memerintah pada saat yang sekarang saya lihat oleh dinasti kepala suku atau raja, masing-masing, seperti Firaun Mesir, pada saat yang sama tinggi imam agama; dan di antara imam-raja kami menemukan satu yang khusus sungguh-sungguh dan fanatik dalam iman yang menyeramkan. Sejauh dapat dilihat pada pemeriksaan singkat, tampaknya tidak ada alasan untuk meragukan bahwa keyakinannya dalam kengerian ini cukup asli; ia memiliki semacam cinta tanah adil Jawa, dan dia benar-benar berpikir bahwa hanya dengan kelangsungan skema mengerikan tentang korban darah setiap hari (yang, bagaimanapun, manusia hanya seminggu sekali, kecuali pada festival khusus tertentu!) bisa negaranya diselamatkan dari kehancuran sepenuhnya di tangan para dewa dengki dan haus darah yang seharusnya untuk mewujudkan kemarahan mereka dalam letusan gunung berapi sering. Kasihan, dia berada di bawah langsung, inspirasi Darker Powers, tapi tentu saja dia sangat menyadari itu, dan mungkin menganggap dirinya sebagai patriot!

Dia adalah seorang pria dari kekuatan besar dan tekad tidak fleksibel, dan setelah bekerja rencana yang mengerikan pengorbanan, ia memutuskan untuk memastikan sejauh yang dia bisa bahwa itu harus dilanjutkan sepanjang zaman belum datang. Untuk itu ia bekerja sistem paling rumit sihir, melemparkan dengan usaha yang luar biasa dan panjang terus kehendaknya semacam mantra pada Pulau-meletakkannya di bawah kutukan, karena itu, bahwa sementara kehendaknya diadakan, persembahan korban-korban seharusnya tidak pernah gagal. Hasil tindakannya masih dapat dilihat baik etherically dan astral, dalam bentuk awan gelap besar melayang rendah di atas pulau, bukan hanya cukup materi untuk dapat dilihat oleh penglihatan fisik biasa, tapi sangat hampir jadi. Dan awan memfitnah ini memiliki penampilan aneh yang “dipatok turun” di titik-titik tertentu tertentu, sehingga tidak hanyut.

Bintik-bintik ini adalah tentu saja khusus magnet olehnya untuk tujuan itu; mereka hampir selalu bertepatan dengan kawah dari berbagai gunung berapi, mungkin karena outlet ini biasanya dihuni oleh jenis aneh alam-roh keuletan yang luar biasa, melihat gambar-perunggu animasi aneh seperti jenis yang khusus rentan terhadap jenis pengaruh yang dia gunakan, dan mampu mempertahankan dan memperkuat itu untuk waktu yang tidak terbatas. Tentu juga Powers Darker siapa, namun secara tidak sadar, ia menjabat merawat untuk memberikan skema nya pendukung seperti mereka bisa dan dengan demikian datang bahwa awan ini masih dalam bukti bahkan pada hari ini, meskipun dengan jauh lebih sedikit dari kekuatan kuno.

Sebuah Invasi Kaum Arya

Penduduk Jawa adalah sangat campuran ras-pada kenyataannya, konglomerasi ras, tetapi semua memiliki secara keseluruhan dominan darah Atlantis. Oleh karena itu mereka berada di hari-hari sebelumnya di bawah yurisdiksi Tuhan Chakshusha Manu; tetapi Dia, menjadi sangat tidak puas dengan kondisi yang ada kemudian di sini, diatur dengan Tuhan Vaivasvata Manu untuk menurunkan serangkaian gelombang imigrasi Arya ke negara itu dengan harapan membawa tentang perbaikan. Paling awal dari gelombang ini dengan yang saya investigasi telah membawa saya ke dalam kontak di suatu tempat sekitar 1200 SM, meskipun saya berpikir bahwa ada upaya telah memiliki sebelumnya; tapi tak satu pun dari mereka dan tidak inflow ini tidak setiap tradisi pasti sekarang tetap di antara arsip kerajaan.

Maskapai penjajah Hindu tampaknya telah datang pertama sebagai pedagang damai, menetap di pantai dan secara bertahap membentuk diri menjadi Serikat komersial kecil yang independen; tetapi dalam proses waktu kekuasaan mereka sangat meningkat, dan mereka akhirnya menjadi bagian dominan dari masyarakat campuran, sehingga mereka mampu untuk memaksakan hukum mereka dan cita-cita mereka atas penduduk sebelumnya. Agama mereka adalah Hindu, meskipun tidak mungkin dari jenis yang paling murni; tapi itu setidaknya merupakan perbaikan besar atas apa yang telah mendahuluinya di sini. Satu akan diharapkan orang-orang dari iman yang lebih tua untuk menyambut dengan antusiasme teori yang akan membebaskan mereka dari kengerian tersebut; tetapi sebagai Sebenarnya mereka tidak tampaknya telah mengambil ramah untuk upacara rumit yang ditawarkan kepada mereka, dan meskipun di bawah rezim baru ritual kuno busuk dan mengerikan dilarang keras, mereka masih luas dipraktekkan secara rahasia. Pemerintah baru menduga ini, namun dikhawatirkan akan membuat upaya yang benar-benar bertekad untuk menegakkan keputusan yang tidak populer; sehingga korban yang tidak berarti dihilangkan, meskipun mereka harus ditawarkan secara diam-diam.

Superstition selalu mati keras, dan lebih kejam dan menjijikkan itu, semakin gigih melakukan votaries yang melekat padanya. Hindu tetap agama resmi negara, tetapi lebih dan lebih sebagai abad bergulir melakukan tua setan-ibadah menegaskan kembali sendiri, sampai votaries yang nyaris bermasalah untuk menyembunyikan praktek jahat mereka, dan kondisi aktual rakyat biasa sangat sedikit lebih baik daripada sebelum invasi.

Ini begitu, Tuhan Vaivasvata memutuskan untuk membuat upaya lain, sehingga Ia terinspirasi penguasa India dirayakan Cincin Ranishka Northwest India untuk menurunkan sebuah ekspedisi ke Jawa pada tahun 78 Masehi Pemimpin perusahaan baru ini dikenal dalam tradisi negara sebagai Aji Saka, atau kadang-kadang Sakāji, dan namanya masih dihormati oleh semua orang Jawa yang banyak membaca.

Dia dikreditkan oleh mereka dengan pemusnahan akhir kanibalisme, pengenalan (atau mungkin lebih tepatnya penegasan kembali yang) hukum dan budaya Hindu, sistem kasta, vegetarian, dari epos Hindu dan aksara Jawa, yang tampaknya berasal dari yang Deνanāgari.

Dia (karena dia adalah seorang ortodoks Hindu), atau lebih mungkin beberapa perwiranya, mendirikan sekolah-sekolah agama Buddha di kedua bentuknya, Hinayana dan Mahayana. Mantan tampaknya telah berlaku selama beberapa waktu, tetapi di bawah kekuasaan Shailendra Kings pada abad kedelapan sekolah yang terakhir datang ke menonjol, dan akhirnya hampir seluruhnya digantikan bentuk Hinayana. Buddhisme cepat dan diadopsi secara luas di pulau, tapi pengikutnya dan orang-orang dari agama Brahmanical tampaknya telah hidup berdampingan dalam persahabatan yang sempurna dan toleransi.

Pusat Magnetic

Sakāji sangat menyadari pekerjaan yang ia telah diutus. Hal ini terkait dari dia dalam tradisi lokal yang di tujuh tempat di negara ia menguburkan benda sangat magnet tertentu untuk menyingkirkan Java pengaruh jahat, berusaha sehingga untuk melawan “menjepit bawah” proses Atlantis imam-raja. Dalam bahasa Jawa ini pesona jahat menghancurkan disebut tumbal, dan fakta keberadaan mereka dikenal di kalangan rakyat negara. Meskipun beberapa prestasi dikaitkan dengannya (seperti penghapusan pegunungan tertentu, dll) mengambil lebih dari karakter buruh dari Hercules, dia sangat jauh dari sekedar tokoh legendaris, dan dia telah menetapkan tandanya di banyak cara pada negara yang ia memerintah begitu tegas. Dia mungkin tidak telah pindah pegunungan, tetapi ia memberi mereka nama-nama Sansekerta dimana mereka masih universal dikenal saat ini.

Sebuah gunung di distrik Jepara, dikatakan tertua dan awalnya elevasi tertinggi di pulau, berada di hari sebelumnya diidentifikasi dengan Μahāmeru tapi Sakāji memberikannya nama Mauriapada-jejak Μaυrya. (1) Dalam waktu itu sudah beenextinct untuk usia, tetapi tindakan vulkanik sekunder masih dalam ayunan penuh. Cina sejarah dari laporan periode terutama lumpur-air mancur menyemburkan ke langit sedemikian tinggi besar di Grobogan, selatan gunung, bahwa pelaut di laut jauh bisa melihatnya dan mengarahkan olehnya. Sekali lagi, di dekat Tuban (kata yang berarti “mengalir”) yang sejarah yang sama menyebutkan baik beberapa mil dari pantai dengan begitu kaya curahan air tawar bahwa air laut untuk jarak tertentu sama sekali tidak garam, atau bahkan payau , tapi bisa diminum dengan impunitas.

(1) Dinasti Maurya dimulai pada 322 SM setelah kematian Alexander. The Capital adalah Pataliputra (sekarang Patna). Kaisar Asoka adalah dinasti Maurya.

Sakāji dipilih untuk penguburan-tempat yang paling penting dan paling kuat nya tumbal atau jimat adalah suatu bukit bulat tertentu rendah, yang terakhir dari berbagai bukit yang menghadap ke sungai Prago-tempat yang, baik dengan desain atau hanya kebetulan , sangat dekat ke titik pusat dari seluruh pulau Jawa seperti sekarang-meskipun tentu saja pada masa Aji Saka posisinya sangat jauh dari pusat, seperti Jawa dan Sumatera yang kemudian bergabung dalam satu. Sekarang siswa Theosophical menyadari bahwa setiap negara memiliki pemerintahan sendiri Deva, yang superintends perkembangannya di bawah arahan Raja Spiritual besar yang dalam literatur kita sering berjudul Tuhan Dunia. Deva ini mengawasi dan sejauh mungkin berusaha untuk memandu evolusi semua kerajaan alam di negara-bukan miliknya manusia saja, tetapi hewan, tumbuhan dan bahkan mineral juga, termasuk tuan rumah besar sifat-roh . Dia memiliki bawahnya sejumlah besar bawahan Deva, biaya masing-masing mengambil dari kabupaten, dan di bawah mereka pada gilirannya adalah roh muda dan kurang berpengalaman, yang belajar bagaimana mengelola masih kecil traktat-kayu, danau, bukit-side .

Ketua Dewa

Semua ini jenis dan tingkat Malaikat yang berbeda hidup di provinsi masing-masing, baik provinsi-provinsi besar atau kecil, dan memang mereka mengidentifikasi diri dengan wilayah mereka dengan cara yang sangat tidak mudah bagi manusia untuk memahami; masing-masing hampir dapat dikatakan ensoul daerahnya, meskipun benar juga bahwa ia selalu dalam wilayah yang tempat tertentu yang dapat dianggap sebagai tempat tinggal khusus. A Deva yang menemukan dalam distriknya gunung sesuai ditempatkan atau bukit sering memilih bahwa sebagai pusat operasinya, dan membuat rumah-begitu nya sejauh semangat melingkupi dapat dikatakan memiliki rumah.

Sekarang pada saat yang sama bahwa Tuhan kita Manu diatur untuk turunnya Aji Saka pada apa sekarang Hindia Belanda, Ia juga menunjuk Deva tertentu ke kantor pengawas spiritual ini kelompok yang paling menarik dari pulau-pulau. Ini memimpin Deva memandang berkeliling provinsi baru untuk tempat tinggal diinginkan, tetapi menemukan bahwa hampir semua gunung sudah pra diantisipasi oleh para pelayan dari Atlantis imam-raja. Berapa banyak Sakāji di otak fisiknya tahu tentang ini, sampai sejauh mana ia dan Deva sadar bekerjasama, aku tidak tahu; tetapi kenyataannya muncul bahwa Malaikat akhirnya memilih untuk tempat tinggal nya keunggulan bulat rendah. Pemimpin Arya dimakamkan pesonanya terkuat di kedalamannya.

Jika kita ingat bahwa jimat yang telah khusus magnet untuk tujuan oleh Manu sendiri, dan bahwa Malaikat dipilih adalah orang yang berdiri tinggi di antara penghuni surga, dan memiliki karena alasan itu telah ditunjuk untuk posisi ini sangat sulit, kita wajib mungkin mulai menyadari apa yang tidak biasa kombinasi kita miliki di sini, dan apa yang sangat kuat pusat bukit rendah telah menjadi. Tak heran bahwa ketika, tujuh ratus tahun kemudian, Shailendra dinasti raja-raja mulai berkuasa di Mid-Jawa dan diinginkan untuk mendirikan sebuah monumen benar-benar hebat untuk menghormati Sang Buddha, semakin sensitif penasihat monastik yang direkomendasikan bukit itu sebagai cocok situs, dan sebagainya muncul struktur indah yang sekarang kita sebut Borobudur.

Perancang Borobudur

Tradisi memberikan nama desainer kain yang luar biasa ini sebagai Gunadharma, dan menyatakan bahwa dia adalah seorang Hindu Budha dari perbatasan Nepal; tapi tentara besar pekerja yang ia bekerja adalah orang Jawa. Sulit untuk memastikan tanggal, tapi saya pikir bahwa stupa selesai pada 775 AD itu saat ini telah disarankan oleh beberapa arkeolog, dan penelitian seperti saya telah mampu membuat konfirmasi ini. Selama abad kedelapan sebuah sekte yang disebut Vrajāsana datang agak mendadak ke menonjol di seluruh dunia Buddhis; didirikan di Deccan, tapi presentasi agama menyebar ke banyak negara, Jawa antara nomor tersebut, dan ada beberapa bukti bahwa Borobudur dibangun di bawah pengaruhnya.

Tidak untuk waktu yang lama, bagaimanapun, adalah bangunan indah ini memungkinkan untuk memenuhi sasaran utama yang pembangun-yang seharusnya menjadi tempat ziarah dan instruksi kepada bangsa-bangsa Buddha di dunia. Pada tahun 915 AD ada terjadi orang-orang lain ledakan vulkanik yang mengerikan yang telah Jadi sering dan jadi secara efektif diselingi sejarah ini bagian dari dunia. Gunung berapi besar Krakatau (kemudian disebut Rahata atau Kanker-gunung berapi) pecah menjadi letusan Begitu hebatnya sehingga membagi seluruh pulau menjadi dua bagian-sekarang disebut Jawa dan Sumatera masing-masing-dan membawa ke dalam keberadaan Selat Sunda. Dalam catatan tertua kita menemukan bahwa jalur perdagangan dari India ke Cina selalu melalui saluran Malaka; tapi segera setelah bumi telah menetap turun lagi dari rasa hormat ini kejang kita mulai mendengar dari penerapan bagian selatan baru melalui Selat Sunda. Bencana mengerikan ini disebutkan dalam prasasti Raja Erlanggha, kadang-kadang disebut Jala-langgha, yang berarti “dia yang berjalan di atas air”-rupanya karena ia melarikan diri dari banjir devasting disebabkan oleh letusan, dan berlindung di sisi dari gunung Lawu besar di Surakarta.

Borobudur Dimakamkan

Pada saat yang sama Gunung Merapi membuang jumlah yang luar biasa pasir dan abu, menghancurkan hampir seluruh Erlanggha Mid-Java kerajaan, dan seluruhnya mengubur (di antara banyak bangunan lainnya) Borobudur,, Mendoot, dan kuil-kuil Prambanan. Tentu jumlah besar cedera dilakukan untuk semua monumen ini; yang dāgοba di atas Borobudur dan banyak baik dari proyeksi lain yang rusak, namun di sisi lain bentuk umum dari bangunan tersebut dipelihara dan batu-batu itu diselenggarakan lebih atau kurang dalam posisi. Selama berabad-abad keberadaan kuil besar ini lupa; jika hanya bisa tetap demikian sampai hari ini, dan telah ditemukan sekarang dengan tangan hati-hati dan penuh hormat, betapa jauh lebih baik itu akan menjadi!

Erlanggha, sehingga tiba-tiba dirampas pada satu gerakan kerajaannya dan pendapatan nya (1), tampaknya telah menjalani kehidupan pribadi dengan beberapa pengikut selama beberapa tahun di lereng Gunung Lawu, di mana akan bertemu dengan beberapa brahmana Vaishnavite yang tinggal di hutan di sana sebagai pertapa. Dia belajar banyak dari mereka dan sangat terkesan dengan doktrin mereka, yang mewarnai seluruh kehidupan masa depannya. Setelah beberapa waktu, bagaimanapun, dia datang dari pengasingan dan membuat jalan ke Jawa Timur, tempat ia akhirnya nasib baik untuk menikah dengan putri Raja Kadiri, sehingga pada waktunya mewarisi tahta lain (2). Dia jelas seorang pria mampu, karena ia mengembangkan kerajaan kaya dan berkuasa di sana di Jawa Timur, di mana (1) Dalam 1007. (2) Dalam 1030.

sejarah pulau kemudian memfokuskan diri; tetapi beberapa abad berlalu sebelum hal itu mungkin untuk kembali menempati Mid-Jawa. Di bawah naungan-Nya Sansekerta belajar membuat kemajuan besar di Kediri dan Janggala daerah, membentang hingga ke delta Brantas, dekat tempat Surabaya saat ini. Buddha dan Hindu berkembang sama di bawah pemerintahannya, dan sama-sama dihormati; pada kenyataannya, untuk sebagian besar mereka tampaknya telah dicampur. Keluarga kerajaan kini Bali dan Lombok adalah keturunan dari Erlanggha.

Semacam tradisi tentang Borobudur harus berlama-lama di antara keluarga kerajaan Jawa, karena ada cerita bahwa Putra Mahkota Djokjakarta mengunjungi tahun 1710; tapi sejauh pengetahuan publik pergi, itu ditemukan kembali, selama pendudukan Inggris pendek Jawa di masa Napoleon, oleh Gubernur Jenderal Sir Stamford Raffles, yang mengambil minat yang besar dalam kuil-kuil dan reruntuhan pulau. Dia memerintahkan penggalian nya, tapi itu segera menemukan bahwa pekerjaan akan waktu bertahun-tahun, dan hanya sedikit telah dicapai ketika tiba saatnya untuk menyerahkan kembali Kepulauan ke Belanda. Pemerintah Belanda memiliki pekerjaan lain dan lebih langsung menekan di tangan, dan penelitian antik tidak serius dilakukan sampai pertengahan abad lalu.

Paling sayangnya monumen taranya ini tidak pada awalnya ditempatkan di bawah perlindungan pemerintah, sehingga beberapa gambar yang dipindahkan ke museum, atau bahkan disajikan kepada pengunjung dibedakan, dan penduduk desa dari lingkungan yang digunakan reruntuhan sebagai batu-tambang, di biadab cara di mana penduduk desa melakukan seluruh dunia. Pada saat ini Pemerintah telah sepenuhnya sadar akan betapa pentingnya kepercayaan mengaku untuk itu, dan telah menciptakan sebuah departemen khusus yang ditujukan untuk perlindungan dan pemulihan reruntuhan. Pemulihan telah dilakukan dengan perawatan yang sangat besar dan penghakiman, menggantikan batu yang hilang di mana mutlak diperlukan untuk mendukung bangunan, tetapi tidak pernah mencoba apapun ukiran atau hiasan, sehingga batu baru selalu batu kosong, dan kami tidak melihat seni tapi periode yang asli.

Βοrobudur

Monumen yang indah yang disebut Borobudur sering digambarkan sebagai sebuah kuil; tapi ini tidak sepenuhnya berbicara benar. Sebuah candi adalah sebuah bangunan kurang lebih seperti sebuah gereja Kristen atau Muhammad masjid-bangunan di mana orang berkumpul bersama untuk tujuan religius, untuk menawarkan ibadah atau doa kepada Dewa mereka, atau untuk mendengarkan penjelasan tentang ajaran agama mereka. Tipe lain dari struktur suci theStūpa atau Dagoba, yang biasanya berbentuk lonceng ereksi yang kuat, dibangun untuk mengabadikan dan untuk menjaga peninggalan Sang Buddha atau orang suci besar lainnya atau guru. Mungkin spesimen terbaik dari hal ini adalah besar Shwe Dagon atau Golden Pagoda di Rangoon-puncak menara emas megah lebih tinggi dari Katedral St Paul di London.

Borobudur memiliki lebih dari karakteristik Stupa dari candi, karena tidak diragukan lagi peninggalan yang pada satu waktu diawetkan di sana; belum

lempeng I

itu tidak seperti yang lain Stupa di dunia, untuk itu dapat disebut gambar-galeri besar, adegan yang tidak dilukis di atas kanvas atau fresco, namun diukir di relief di batu, dalam serangkaian panel indah presisi di seluruh, dan banyak dari mereka benar-benar indah. Ada 2141 ini, dan itu dihitung bahwa jika mereka ditempatkan ujung ke ujung mereka akan memperpanjang selama hampir tiga kilometer.

Mungkin cara terbaik untuk mewujudkan Borobudur adalah untuk menganggapnya bukan sebagai sebuah kuil atau sebuah stupa, tetapi sebagai sebuah bukit bulat rendah berselubung dengan batu. Batu asli bukit membentuk inti dari seluruh ereksi, yang hanya dibangun untuk itu di teras berturut-turut. Pengaturan ini akan dipahami dengan memeriksa terlebih dahulu pandangan Borobudur dari udara (pelat I). Kita melihat dari foto udara bahwa seluruh kain dapat dikatakan terdiri dari tiga bagian yang terpisah. Ada pertama dasar persegi di mana seluruh bangunan berdiri, masing-masing sisi alun-alun seluas 620 ft .; dan bahkan yang akan terlihat benar-benar ganda, yang terdiri dari dua platform. Platform ini memiliki simbolisme mereka sendiri, yang saya akan merujuk saat.

piring II

Dari dasar ini naik bagian kedua dari bangunan tersebut, yang terdiri dari empat tahap persegi panjang, masing-masing teras luas atau galeri antara dinding, tapi terbuka ke langit. Hal ini pada dinding ini yang kita temukan yang indah

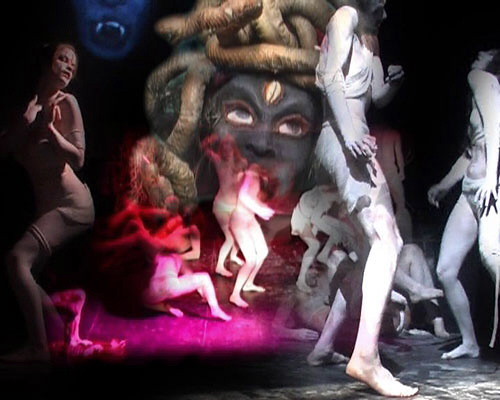

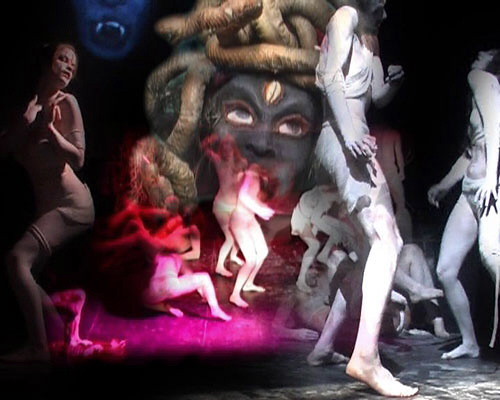

ukiran yang telah saya sebutkan (pelat III), naik di kedua tangan seperti yang kita berjalan di sepanjang galeri-biasanya dua baris panel satu di atas yang lain. Baris atas relief di dinding kepala galeri terendah diwakilinya dalam rangka kisah kehidupan terakhir dari Tuhan Gautama, seperti yang diberikan dalam buku Sansekerta disebut Lalitavistara, sedangkan adegan lain dipahami untuk menggambarkan ajaran-Nya di tahap berurutan dari surga dunia. Kita melihat divisi tiga bangunan-tiga platform melingkar dan Dagoba pusat besar (Plat I).

Tidak diragukan lagi tujuh tahap ini dimaksudkan untuk mewakili tujuh pesawat. Arkeolog Belanda terkenal, Profesor Krom, menulis dalam Kehidupan nya Buddha ::

“Sesuai dengan makna kosmik bangunan galeri yang kaya dekorasi, tapi platform yang, berbeda dengan dunia fenomenal di bawah ini, dimaksudkan untuk mewakili wilayah tak berbentuk, telah ditinggalkan tanpa hiasan. Relief mewakili teks yang dimaksudkan untuk mengesankan pelajaran kebijaksanaan dalam pikiran orang percaya saat ia menaiki stupa, dan sehingga untuk mempersiapkan dirinya untuk pencapaian wawasan tertinggi bahwa Mahayana membawa depan matanya. Dengan cara ini ia juga membawa rohani ke pesawat yang lebih tinggi saat mendekati Stupa tengah “(hal. Viii).

Terlepas dari ukiran dan cerita mereka, ada dalam empat galeri 432 patung besar dari Sang Buddha berkisar secara berkala sepanjang bagian atas dinding, masing-masing duduk di niche sendiri atau tersembunyi suci (Plat IV). Semua 108 gambar pada setiap sisi duduk dengan mudra yang sama atau tanda tangan (pelat V). Di Utara, mudra adalah bahwa yang disebut Abhaya-Jangan takut; di Timur, mudra adalah Bhūmisparsha-Menyentuh bumi; di Selatan, Dana-Giving; di Barat, dhyana-Meditasi.

Seperti yang akan terlihat dari pelat VI, pada masing-masing platform melingkar kita menemukan cincin patung Tuhan, 72 di semua; tetapi dalam kasus ini masing-masing patung duduk di dalam Dagoba kisi-kerja atau kubah batu. Kisi-pekerjaan berbeda pada platform ini, lubang yang kadang-kadang persegi dan kadang berlian berbentuk, dan saya membawa mereka sebagai dimaksudkan untuk melambangkan (serta dapat dilakukan dalam batu) transparansi mengagumkan dan kelezatan munculnya aura atau kendaraan laki-laki pada tingkat yang lebih tinggi.

lempeng IV

plat V

lempeng VI

lempeng VII

Para biarawan senior Buddha Sangha digunakan untuk memimpin murid-murid mereka dan mereka pilgrim-pengunjung dari panggung ke panggung gedung, memberikan serangkaian kuliah pada kehidupan dan ajaran Tuhan, dan menggunakan ukiran sebagai ilustrasi. Tetapi untuk siswa yang lebih maju mereka juga menguraikan teori tujuh pesawat, dan belum lebih lanjut, dari tujuh prinsip manusia, menggunakan tiga lingkaran dan empat kotak sebagai emblem, sama seperti kita saat ini menggunakan segitiga dan persegi untuk menandakan atas Triad dan Bawah Kuarter.

Seluruh bangunan ini diatasi oleh kubah yang lebih besar, lima puluh meter dengan diameter, dimahkotai oleh puncak menara rusak (Plat VII). Kubah ini awalnya berisi kotak kecil atau stoples abu (yang memiliki, namun, lama dicuri) dan juga patung yang belum selesai penasaran dari seorang Buddha. Teori banyak arkeolog adalah bahwa hal itu dimaksudkan untuk melambangkan Amitabha, dan sengaja dibiarkan belum selesai, untuk menunjukkan bahwa Tanpa Batas Cahaya tidak dapat diwakili dalam bentuk manusia, tetapi hanya bisa menyarankan-itu, sebagai Mr Banner mengatakan di Romantic nya Java: “skill Mortal mungkin tidak menganggap untuk mewakili dalam kelengkapan Nya All-tertinggi”. Penulis yang sama juga menyatakan:

“Yang terendah dari teras miring dihiasi dengan ukiran perwakilan dari adegan biasa yang umum, untuk menekankan moral yang di atas bumi beristirahat semua nilai-nilai spiritual yang tinggi. Tapi setelah kedua dinding dari empat galeri di sana-setelah kami menemukan serangkaian terus menerus bas-relief yang menggambarkan fenomena keagamaan di gradasi menaik. Galeri pertama, artinya, menampilkan pilihan adegan dari sejarah kehidupan Buddha; kedua menunjukkan dewa kecil dari ibadah Brahmana diadopsi ke dalam Buddha Pantheon; ketiga berisi para dewa yang lebih tinggi, di pesawat di mana kuil daripada dewa itu sendiri disembah; sementara di keempat kita menemukan hanya kelompok Dhyani-Buddha. “(1)

(1) Op. cit., p. 126.

Apakah detail dari pernyataan ini benar saya tidak bisa mengatakan, karena saya tidak cukup mengenal dengan indikasi menit dimana spesialis dalam arkeologi menganggap bahwa mereka mengenal berbagai jenis Buddha; tetapi ide umum sesuai dengan banyak yang saya lihat.

Alun-alun Platform ganda di mana struktur yang luas seluruh bertumpu benar-benar membuat panggung lain di bawah permukaan bumi, di mana ada serangkaian rumit ukiran yang mewakili berbagai lokas-jelas pesawat astral lebih rendah, yang sebenarnya tidak menempati persis bahwa posisi dalam ruang . Hal ini seharusnya oleh beberapa tahap terendah ini pada awalnya dimaksudkan untuk menjadi terbuka ke udara persis seperti yang lain; arkeolog lain mengklaim bahwa itu selalu dimaksudkan untuk menjadi bawah tanah untuk melambangkan “neraka,” tapi itu suatu bagian berkubah luas berlari bulat di depan ukiran, sehingga mereka bisa dilihat. Jejak bagian berkubah ini dikatakan ada, namun ketika tempat itu ditemukan oleh orang Eropa itu sudah diisi oleh blok besar batu. Teorinya adalah bahwa berat besar incumbent batu Super menyebabkan seluruh struktur untuk mulai menyelesaikan bahkan sebelum itu selesai, dan bahwa pembangun harus karena itu untuk mengorbankan tahap terendah untuk menyelamatkan keseluruhan. Dengan kata lain, terlihat bahwa dasar tidak akan cukup kuat untuk mendukung keseluruhan, sehingga untuk memperkuat basis itu, band besar batu dibangun bulat seperti cincin batu raksasa, yang sekarang platform persegi.

Di tengah masing-masing dari empat sisi alun-alun tangga curam naik, pintu gerbang ke setiap tangga dijaga oleh singa duduk, dan direntang oleh lengkungan hiasan kesempurnaan arsitektur tertinggi (Plat VII). Dari dasar platform yang persegi ke paling atas dari platform melingkar tapi 118 ft. Tinggi tegak lurus, sedangkan perimeter seluruh piramida berdiri pada platform yang lebih rendah adalah 2.080 ft., Sehingga seluruh kompleksitas galeri, dengan kekayaan yang membingungkan mereka ornamentasi, membuat banyak-datar setengah dunia, yang kontur terhadap langit adalah kurva yang sempurna. Bahkan, sebagai salah satu penulis yang unpoetically mengatakan, pekerjaan telah dilakukan sehingga terampil bahwa dari jauh struktur tampak tidak seperti hidangan penutup yang sangat hiasan!

Ini adalah gundukan hanya dibandingkan dengan Shore Dagon (Rangoon), atau reruntuhan luar biasa di Angkor Wat-(Indo-Cina), tetapi dalam rinciannya itu jauh lebih indah dan indah dari salah satu dari mereka. Mr Scheltema, dalam buku Jawa Monumental nya, menggambarkannya sebagai “pencapaian yang paling sempurna dari arsitektur Buddha di seluruh dunia”; dan di tempat lain ia berbicara tentang “keindahan supernatural Borobudur.” Profesor Krom, yang saya sudah dikutip, menyatakan bahwa Borobudur merupakan salah satu dokumen yang paling terkenal dan monumen keagamaan seni Buddha, dan bahwa ereksi arsitektur yang sangat indah ini melampaui semua karya seni yang satu menemukan di Timur. Dr Krom sendiri, yang dinyatakan materialis, begitu terpengaruh oleh keindahan Borobudur yang ia mengatakan bahwa atmosfer yang dipancarkan oleh monumen ini begitu luar biasa karena inspirasi ilahi yang dipandu tangan yang berbentuk itu.

[Catatan oleh C. Jinarājadāsa: saya pertama kali melihat Borobudur di 1919 Sejak itu saya telah mengunjungi monumen dua kali. Saya telah mendalam terkesan dengan salah satu kualitas khusus dari konsepsi besar arsitek. Monumen ini terkait dalam pikiran saya dengan keajaiban India, Taj Mahal. Ada baik kualitas biasa dari kesatuan transendental, dan di samping sesuatu yang hampir supranatural. Hal ini seolah-olah setiap monumen yang benar-benar besar bentuk-pikiran-in granit di Borobudur dan marmer di Agra, dan bahwa ini bentuk-pikiran turun ke bumi dan berpakaian sendiri dalam hal. Ini menjadi maka monumen yang kita kagumi. Dalam kasus kedua Borobudur dan Taj Mahal, ada perasaan bahwa jika beberapa penyihir yang melambaikan tongkat sihirnya, setiap monumen akan secara keseluruhan hanya naik ke atas ke langit dan menghilang. Saya tahu tidak ada monumen lain yang memiliki kualitas spiritual yang tidak biasa ini. Mungkin Parthenon di Athena memiliki kualitas sihir yang sama.]

Sebuah setengah mil dari Borobudur adalah candi dari Mendoot-bangunan yang, meskipun sangat jauh lebih kecil dari yang lain dan memiliki cukup tujuan yang berbeda, adalah jelas dari periode yang sama dan menunjukkan kombinasi yang sama dari kebahagiaan dalam desain dan presisi dalam pelaksanaan . Kali ini bangunan ini benar-benar sebuah kuil, yang berisi tiga patung besar, yang secara praktis mengisinya;and one may see that even at the present day the peasants of the neighbourhood still pay reverence to them, and lay before them daily offerings of flowers.

The temple was apparently originally a structure of brick, but round that some eleven or twelve hundred years ago was built a stone outer sheath, scrupulously following the older design in all its complicated details of panellings, and of horizontal and perpendicular projections. It stands in the middle of an elevated platform, and its exterior is decorated with excellent carvings such as those at Borobudur, but in this case they illustrate not the life of the Lord Buddha but certain ancient folk-tales or popular legends, of the order of Aesop’s Fables. The building has a high pyramidal roof which, I am told, shows remarkable skill in vaulting. It is supposed that there was originally some sort of dāgoba-like top or spire as a finish to the truncated pyramid, but as no traces of this now remain, the restorers have not ventured to make any attempt to reproduce it (Plate VIII).

A broad flight of steps leads up to a high and rather narrow doorway, on entering which the traveller finds himself in a lofty square room in the presence of the three great statues to which Ι have already referred, sitting with their backs to the three walls, precisely as though they were gathered round a table in conversation; but there is no table (Plate IΧ). As we enter, the image of the Lord Buddha faces us, while that shown on our right is a Bodhisattva. The statue in the middle, which by many marks is clearly intended for the Lord Buddha, is fourteen feet high in its sitting position, while the other two are only eight feet from top to toe as they sir. (1) Originally, therefore, the central statue must have towered above the others, but its enormous weight has caused its base to subside considerably, so that now they are almost on a level.

(1) As the two images to the right and to the left wear crowns, they represent Bodhisattvas.Often the crown of a Bodhisattva has a small Buddha image carved on it, as a sign that the Bodhisattva will later become a Buddha.—C. J.

Plate VIII

Plate IX

Several curious things may be noted in connection with these statues. They are not in the least the traditional half-Mongolian Buddha figures; the faces are clearly Aryan, and also quite individual—indeed, they are supposed to be portraits. The Lord Buddha is seated as a European and not as an Asiatic, and the others are at least halfway between the two postures. The edge of the Lord’s robe is conventionally indicated by a line, yet it does not seem to conceal the rest of the body. Both of the other statues are much more ornately dressed, wearing necklaces, armlets, wristbands, anklets and tiaras; and it is remarkable that these ornaments are far more Brahmanical than Buddhistic in character.

There is much dispute among archeologists as to the identity of these other figures, and no reliance can be placed upon the names of Padmapāni and Manjushrī, which are often attached to them by the photographers. The curator who was in charge of Mendoot on my first visit—a very able man who was exceedingly kind and helpful—professed himself as fairly certain that the figure on the left of the Lord (but of course on our right as we look at them from the doorway) was intended for the Lord Maitreya; I myself for various reasons rather inclined to the idea that the other image, seated on the right of the Lord, may have been meant for the great Bodhisattva. The little figure hovering over the head of that statue is usually explained as a Dhyānī-Buddha overshadowing the earthly manifestation.

There is a strong belief among the Javanese noble families (who have many interesting traditions of the past) that there is an underground passage from Mendoot to Borobudur, leading into a subterranean Temple of Initiation which, they assert, exists under the latter —a passage which was intentionally closed at a later date. Dr. Brandes, an archeologist of high reputation, discovered in the course of his excavations a red-brick building under the foundations of Mendoot, but was unable to continue his investigations because they endangered the stability of the whole edifice. It is supposed that Mendoot was the central shrine (the private chapel, as it were,) of a great group of monasteries occupied by the host of monks attached to Borobudur.

Telaga Warna

A True Story of Java

THREE Initiates stood on the brink of a lonely pool. Far from all human habitation—the nearest being a small group of huts used by a few uncultured labourers working upon a vast plantation—the whole place was steeped in the marvellous pregnant silence of the tropical noon. It seemed as though all the world lay dozing in the glow of that splendid sunlight, waiting to waken to a more active life when the cool dews of evening should descend upon the expectant earth.

This tiny lake is on the shoulder of a mountain; it is surrounded and shut in by noble trees, but not far away, through a break in the forest, one can look out over miles of undulating plain with little sign of human occupation. A road passes within easy reach of this magic spot, but travellers are few, and the deep peace of the district is but rarely disturbed by the uncouth gruntings of a climbing motor.

This pool is of no great size—perhaps not much more than a hundred yards across; it is what in Scotland would be called a tarn; the peasants regard it as a sacred lake, and it lies like a lovely gem in the green setting of the forest trees. On the opposite side of it there rises, abruptly an almost perpendicular cliff, probably seven or eight hundred feet in height, just not too steep to be clothed with a perfect curtain of trees and bushes—a wonderful and most beautiful hillside. The water is absolutely still, sheltered and unruffled.

It should be—it is now—a scene of uttermost peace, a haven of calm for a troubled spirit; but at the time of the visit of the Brothers of whom I spoke, there was about it a curious feeling of unrest, of long-enduring melancholy and remorse, hoping for relief, yet hardly daring to expect it. Looking round for the source of this strange sadness, our Brethren found that it emanated from the Spirit of the Lake, who was a Devī—that is to say, a spirit with a distinctly feminine appearance. We know that in the Deva kingdom there is nothing corresponding to sex as we know it on the physical plane, but assuredly some Angels have a virile and essentially masculine aspect, while others look just as definitely feminine, and this was one of the type last-mentioned.

The Brethren felt very strongly that she was waiting for something—waiting rather hopelessly, and with a sickening sense of intense regret. Our Brothers watched her very closely for a few moments, and one said to another:

“For whom is she waiting? It cannot be for us, though I thought at first that it was.”

“No,” replied the other; “but she has done something—something that makes her very sad, and she hoped for a moment that we had come to put it right.”

They were all conscious that there was a very fine and a very kindly Deva on the summit of that steep hill-side just across the pool, and that he was watching over the Lake-Spirit’s trouble with great solicitude and tenderness. Naturally, our Brethren expressed the deepest sympathy, and asked as delicately as possible what was the matter, and whether there was anything they could do to help.

In response the Lake-Spirit thanked them rather wearily and brought before them a. succession of scenes—which, you know is a Deva’s way of telling a story, a sort of astral and mental cinematography—from which our friends acquired the outline of her tale of woe.

It seems that that country had long ago been for centuries under very evil influences connected with Atlantean black magic; later there had been an Āryan invasion which introduced great improvements in religious matters, but for a long period both forms of belief and practice existed simultaneously, and even now in the twentieth century relics of the more ancient faith are to be found in remote places, as I can personally testify.

There was a time, not so very long ago, when the land was parcelled out among a number of petty Āryan chieftains or Rājas, whose dominions were in many cases hardly larger than the more modern German Grand Duchies; but these distinctly minor kings were (softly be it spoken) just as proud and arrogant as though they had been Chakravartins—the rulers of mighty empires! There were also living in the country descendants of the old Atlantean royal race, who were still deeply venerated by the peasants, but were of course despised with truly Āryan intolerance by the scions of the conquering race.

It appears that once upon a time the son of the local Rāja had the bad taste (from his father’s point of view) to fall in love with one of these Atlantean princesses—not a bad-looking person by any means, and of very kindly and affectionate disposition. Of course the Āryan father behaved as fathers so often do under such circumstances; he would not hear of such a marriage at any price, and fell into a violent fury; so the unhappy young people ran away together in the best traditional manner, with the avenging parent hot-foot upon their trail, breathing all kinds of fire and slaughter. The lovers fled in great disorder, and just when they came into the neighbourhood of the lake the lady began to feel faint, in the inappropriate way which Victorian ladies frequently adopted at critical moments; and so the irate father overtook them, or at least was in sight and on the point of doing so.

The Devī of the Lake seems to have been at that time an inexperienced person, young at her work. She knew quite enough of Atlantean centres and methods to be aware that there were spirits in connection with other lakes and woods who made an obscene sort of livelihood by receiving sacrifices and inducing people either to drown themselves or to throw their enemies into a lake, as the case might be; and she seems to have felt a kind of envy of the power gained by these foul entities, or at any rate a strong curiosity to try an experiment and see whether black magic was really quite as dreadful as the Deva on the hilltop had always said it was.

So just when the young couple were full of despair she impressed upon their minds a very powerful suggestion that they should throw themselves into the lake, thus dying together and ending all their troubles. Under their desperate circumstances the idea commended itself to the half-crazy lovers, and in a few moments the tragedy was over, and the father was left weeping upon the bank, like Lord Ullin in the Scottish version of a very similar story:

Come back, come back, he cried in grief

Across the stormy water,

And I’ll forgive thy Highland chief,

My daughter! O my daughter!

The Spirit of the Lake shrank back in horror, realizing in a moment the awful result of her unhallowed desires; and she had been mourning about it ever since, not knowing what to do in the way of atonement. It seemed to do her some good to tell her story, or at least to exhibit it in a series of pictures; and the Brethren did their best to comfort her, explaining that the past was past and could not be recalled, and that the only thing to do now was to try to make some kind of compensation by radiating peace and goodwill upon all those who came to visit this lonely spot. They then gave her a Blessing and exchanged courteous greetings with the Deva of the hilltop, who thanked them very heartily for what they had done.

Across the stormy water,

And I’ll forgive thy Highland chief,

My daughter! O my daughter!

The Spirit of the Lake shrank back in horror, realizing in a moment the awful result of her unhallowed desires; and she had been mourning about it ever since, not knowing what to do in the way of atonement. It seemed to do her some good to tell her story, or at least to exhibit it in a series of pictures; and the Brethren did their best to comfort her, explaining that the past was past and could not be recalled, and that the only thing to do now was to try to make some kind of compensation by radiating peace and goodwill upon all those who came to visit this lonely spot. They then gave her a Blessing and exchanged courteous greetings with the Deva of the hilltop, who thanked them very heartily for what they had done.

A few months later the Brethren visited the Lake again, and were delighted to find that a great change had taken place in the condition of affairs. The Deva and Devī are now in much closer friendship than before, and are therefore able to do much better work for the ruling Angel of the whole mountain, who is a very great person, and one of the principal lieutenants of the Deva-King of that country—its national Angel. So the apparently casual help given to the attendant Spirit of a small and lonely lake has had far-reaching and important results.

I have heard since that that little pool is called Telaga Warna, and I am told that Telaga means lake, and that Warna is a corruption of the Samskrit varna, which means colour or caste—because originally the different castes were distinguished by the fact that the Āryan had intermarried with various lower races, and so there was between them an actual distinction of colour. As the whole point of the story depends upon the father’s horror of an intermarriage between different castes and different religions, it seems to me that we have a kind of indirect reference to that story in this popular name.

Air Nature Spirits

C. W. LEADBEATER, describes his first aeroplane journey, from Brisbane to Toowoomba, in August 1928 [Ed. Note—edited from The Australian Theosophist Aug 1928], as follows:

“The air spirits seemed to hail us with riotous joy; they clustered around us and circled at our prow just as I have often seen dolphins behave round the bows of a steamer. We were flying at a very fair speed, but these creatures circled round us with the utmost ease, as though they did not feel the air pressure at all. They gave me the impression of being extremely friendly and well-disposed, and did not in the slightest degree resent our intrusion upon their domain. Curiously enough, however, I caught sight of some other creatures higher up—much higher up—who seemed by no means so friendly. They were of immense size and looked somehow far more material than the sylphs. They were curiously sullen in appearance, and I rather wondered what sort of reception they would have given us if we had risen into their immediate neighborhood. I did not much like the look of them; they reminded me uncomfortably of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s powerful story ‘The Horror of the Heights’. But after all they may have been quite harmless, though sulky.”

Angelic Co-Operation

At The Dasara Festival At Mysore

[Each year at the Festival observed throughout India, called Dasara, which lasts for ten days, the Mahārājah of Mysore holds various ceremonial functions. A few invited guests can also be present. At one of them he receives all the State officials who, dressed in their State uniforms, present to him certain traditional gifts, which however he only "touches and remits". On another day there is the pūja and blessing of all the State animals—elephants, camels, horses and bullocks—of automobiles and all the coaches and carts, of the State umbrella, and of all the equipment and articles used by the Palace household, and so on. One afternoon there is a great procession through the principal streets of the city, when the streets are lined with the subjects of the Mahārājah. (1) He rides slowly in procession, sometimes

[Each year at the Festival observed throughout India, called Dasara, which lasts for ten days, the Mahārājah of Mysore holds various ceremonial functions. A few invited guests can also be present. At one of them he receives all the State officials who, dressed in their State uniforms, present to him certain traditional gifts, which however he only "touches and remits". On another day there is the pūja and blessing of all the State animals—elephants, camels, horses and bullocks—of automobiles and all the coaches and carts, of the State umbrella, and of all the equipment and articles used by the Palace household, and so on. One afternoon there is a great procession through the principal streets of the city, when the streets are lined with the subjects of the Mahārājah. (1) He rides slowly in procession, sometimes

(1) When I saw this procession there was not a single policeman about to keep the crowd in order, as was the case in British India.—C. J. carried in a sedan-chair litter, sometimes mounted on the beautiful white State horse, and at certain points the priests come forward with offerings. He stops for a moment to "receive" them, i.e., to touch them, and then passes on.

The Mahārājah of Mysore, the predecessor of the present Mahārājah, was deeply religious, and several afternoons of each week he would drive to Chāmundi Hill, where there is the temple of the patron goddess of Mysore, the Goddess Chāmundi, who is one embodiment of the Goddess Pārνatī, the consort of the God Shiva. There he would divest himself of his ordinary garb, and dressed in a dhoti as a pious Hindu would sit in meditation. The subjects of the Mahārājah had profound veneration fοr him, and whenever there was an opportunity, as at the public procession, they expressed it, in silent reverence with joined palms.

What happened in the occult world on one of these occasions in 1933 is here described by C. W. Leadbeater.—C. J.]

I ought perhaps to premise that what most especially engaged my attention was the fact that a reigning monarch took a leading part in all the ceremonies. Having studied occultism for half a century, I have learnt that there is a tremendous inner reality behind the idea of “the divinity which doth hedge a King,” and that, though probably he hardly .ever realizes it, he is just as truly set apart and consecrated for his position under the august Head of the First Ray as is an Archbishop for his quite different work on the Second Ray. Through each there flows the influence peculiar to his Ray; for each there is the same distinction, so little understood, between the power thatmay flow and the power that must flow. Let me try to explain what I mean.

I can do so best by employing an analogy, drawn in this case from Christian sources. The great majority of Christians accept the doctrine of Apostolic Succession; that is to say, they know that in order to perform certain ceremonies and to do certain work a Priest must be duly ordained. The power effectively to perform those ceremonies and to do that work is conferred upon him by a duly authorized official, and that power, once given, cannot be withdrawn. An ordained Priest may be, for sufficient reason, deprived of his position and its emoluments, if any, but he cannot be deprived of his priestly power. That this doctrine is understood and accepted by the Church may be seen by the perusal of the 26th of the Articles of Religion of the Church of England “On the Unworthiness of the Minister, which hindereth not the Effect of the Sacrament”. This may seem startling to some, but is really logical and reasonable; he who wishes for an explanation of this is referred to The Hidden Side of Things or toThe Science of the Sacraments, in both of which this matter is treated fully.

From this it follows, however strange it may seem, that a Sacrament may be effectually administered by a Priest who is far from understanding it, or is even of doubtful character; that is the power or influence that must flow through him because of his ordination. But it is obvious that along with this a great deal more may and indeed must flow through a really good and earnest Priest who is devoted to his holy work, and does it with full heart and understanding. Still more is this true of his superior officer, the Bishop or Archbishop; indeed, it is expected of the Bishop that he shall be a perpetual fount of blessing wherever he goes—a true follower and representative of the Head of the Second Ray.

What I wish to emphasize is that a precisely similar attitude is expected from a King—that he has a similar consecration (at the time of his coronation), a similar power, a similar duty; but with this very important difference, that his work lies on the line of the First Ray instead of the Second.

His function is to rule, to guide, to guard, and when necessary to restrain; the virtues on which he lays most stress are truth, justice, strength and courage, whereas those emphasized by the Second Ray are love, gentleness, and compassion. One is concerned principally with physical life and its circumstances, the other chiefly with spiritual development. Wisdom is equally necessary on both lines.

The special work of the Priest or the Bishop constantly brings him before the public in the exercise of his power to bless, so I have frequently had the opportunity of watching the mechanism of the Second Ray in action, even apart from my own work in the Church; but it is not so frequently that the chance comes in one’s way to see the royal function in operation on a large scale. Also, not every King is aware of the full scope of his power, and so he may not use it intentionally.

The “tongue of good report,” however, had universally been heard in favour of His Highness the Maharajah of Mysore; every one spoke of him as an enlightened sovereign, religious by nature and anxious to do his duty to his people; so it occurred to me that it would be of interest to observe the play of forces around him on the occasion of this great public function.

The entry of the Mahārājah into the Audience Hall was exceedingly impressive. The Mahārājah certainly had an escort—in fact he had a double escort, one visible to all, the other and much larger probably seen by few. First, a distinct aura or wave of influence preceded him. He has a very fine aura of his own, this monarch; but it is not to that that I am referring. He was attended by various Devas, and the effect produced at the time of this entry was as though these Devas had thrown an enormous extra faintly luminous aura around him like a great cloud, so that it extended far before him, and as it were pushed its way into the vast crowd waiting for him. It seemed for the moment to absorb, or perhaps better still to infiltrate, all the auras of those present—not so much changing them as vivifying, intensifying, one might almost say electrifying them, undoubtedly preparing them more readily to receive other influences more personal to himself. He could have had no personal volition in manipulating this; it was done for him by those attendant Devas, but it sent a thrill through the whole of that vast crowd although some of those present were much more strongly affected by it than others.

When he himself came in sight, it was at once observable that he and his double escort (physical and astral) were walking in the midst of a globe of light of the same nature as the aura which had preceded him, but far more brilliant. This globe moved with the party, but was entirely distinct from the individual auras of the sovereign and the Angels and men surrounding him. Those auras are of course permanent, whereas the globe gave the impression of being specially formed for the occasion. When the Mahārājah reached the foot of the throne he paused for a few moments, and then walked round it, which seemed slightly to check the flow of the force, but on the other hand produced a strong magnetic effect—a sort of preliminary cleansing.

Then he ascended to the throne, and as his gaze swept over that vast assembly, one felt that he was as it were entering into his kingdom, making a strong personal link with all who could respond to him, in an intimate way which had been rendered possible only by that preliminary action of his Devas in sending out the influence before him. One felt that thereby he held his audience within his grip, so that the active beneficence mentioned could be applied and materialized in their hearts. His Angel escort was industriously co-operating in all this, and its members contrived to keep up something of this feeling in many of his subjects all through the long ceremony which followed. Having made this link with their help, and sent a real wave of enthusiasm sweeping through the hearts of his people as they heard their National Anthem, the sovereign seated himself, and the crowd gradually settled down also.

Then the proceedings began, as described by Miss Kellett; but meantime the Deva attendants who had been floating round and above the throne brought into action a curious astral construction, the like of which I have not hitherto seen. They produced an object which I can only compare to a gigantic, sparkling, diaphanous crown, perhaps six feet or thereabouts in diameter, the base of it being the usual circular ring, but the upper parts rising apparently into a number of points resembling rather an earl’s crown than that of a King. This strange shape they held in the air some distance above the head of the ruler, so that it interpenetrated the golden canopy or roof of the throne. Into this there seemed to flow from above what I can describe only as a kind of stream of soft, liquid light, which seemed to be absorbed by—to charge as it were—the form seated on the throne. When the Mahārājah stretched out his hand to touch something, a flash of this soft light passed from him to the person or object touched, and in the case of some of the recipients it evoked a certain outpouring in reply; but this varied greatly in volume, in colour and in brilliance with different people—I imagine according to their receptivity. It was evidently this scheme which enabled him to endure the fatigue of the ceremony, and yet “to give unto the last even as unto the first”.

The Durbar on the ninth night is the only one in which European guests participate. On this occasion they are presented to His Highness and receive from him a gift of flowers—garlands for the men and bouquets for the ladies. This night is more specially than the others a mere social function—there is about it less solemnity, because the Western element is so foreign to the surroundings.

I can well understand this feeling of “less solemnity,” for there was practically no inner side to this part of the function. The sovereign was attended by his usual Deva escort—I presume that is always with him—but that strange sparkling fairy-like, floating crown was not made, and the wonderful living light of yesterday flowed very sparingly, and received scarcely any response, save in one or two cases. The Mahārājah was still every inch a king, but it was obvious that he was not their king, though quite genial and kindly disposed towards them.

The concluding procession was again a most interesting example of the whole-hearted co-operation of the Angel kingdom with the human. I do not know exactly from what point of view His Highness the Mahārājah regards that procession, but I am able to say that the Deva helpers look upon it as a grand final demonstration intended to impress permanently on the minds and hearts of the people the lessons which they have been trying to inculcate. Their efforts are always directed to the general upliftment of the masses whom they are trying to help, and they regard the affection and devotion which the people feel for their ruler as very important factors through which they can be influenced for good. Al] through the ten days of the festival they have been trying to strengthen such feelings where they already exist, and to awaken them where they do not, and they hope, through the emotion excited by the magnificence of this final procession to stamp these ideas so deeply upon their people that they will not fade out until the next great festival comes to revivify them.

In trying to understand the work of the Devas, we have always to bear in mind that selfishness is absolutely unknown among them; they regard its frequent manifestation by humanity as a kind of terrible disease which must be eliminated at all costs. Therefore they are always working to increase contentment and fraternal feeling in humanity, and it is in that direction that they have been moving through all the days of this prolonged festivity. They see readily that there is much in the hardness and the competition of the daily life of man which by its constant pressure tends to deaden these finer feelings and gradually to erase them, and so they wish to use this culmination of the feast to retain the level just gained.

Therefore the promoters of the movement call together a vast host of minor Angel friends to hover over and increase the joyousness of the procession, so that amidst a very surfeit of physical-plane attractions a shower of benediction may be poured out through it as it passes along. There is also the idea of strongly magnetizing the road which is taken, so that it may continue to influence those who use it. Once more the Mahārājah is the centre of all this influence, and it is through him that the greatest of the blessings are outpoured.

What is there that we can learn from all this? Happily most of us are not called upon to bear the heavy burden of a royal crown; yet there are many among us who are kings in a small way—employers on a more or less extensive scale, heads of departments or offices. We cannot hope to wield the widespread influence of a monarch, but we can make happier or less happy the lives of those over whom we find ourselves temporarily in control, and we know of the promise that he who is faithful in small things will presently have the opportunity to extend that faithfulness to something greater. If we find ourselves in a position of authority, it is assuredly our duty to see that the work for which we are responsible is properly done; but that can be achieved far more efficiently by kindness and persuasion than by roughness. We must learn to work not through fear but through love; so shall we deserve the angelic co-operation, and, deserving it, be sure that we shall receive it.

It was extremely interesting to me to find so marked a case of this angelic co-operation. It seems to me to show that if ever we are happy enough to reach a stage in which all the world will work together in that way along similar lines, the help of the higher evolution of the Deva Kingdom will undoubtedly be extended to us in many ways of which at present we have no conception….

****************************************

The Occult History Of Java

By C. W. Leadbeater 1951

THE THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE

ADYAR, MADRAS 20, INDIA

CONTENTS

PAGE | |

The Occult History of Java | 1 |

Borobudur and Mendoot | 20 |

Telaga Warna | 35 |

Air Nature Spirits | 43 |

Angelic Co-operation | 45 |

Printed by D. V. Syamala Rau, at the Vasanta Press,

The Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras

The Occult History Of Java

History

THE early history of Java appears to be wrapped in mystery. From reading most of the books written in English on the subject one would infer that the Island was entirely unknown to the rest of the world until it was visited by the Chinese pilgrim Fa Hien in the year 412 Α.D.; and even after that there are at intervals gaps of several centuries which it seems at present impossible to fill by any ordinary means. Ruins are plentiful, but scarcely any of them are more than 1200 years old, and very few records or inscriptions have been preserved. Certain traditions have been handed down among the princely Javanese families; but even those become distinctly apocryphal as we follow them back to the beginning of the Christian era, and beyond that they are mere incredible legends. Perhaps that need not surprise us, for after all we can trace the history of England no further!

By calling in the aid of clairvoyance we can of course carry our investigations back indefinitely, but for our present purpose it will suffice to try to examine the conditions existing in the country somewhere about 2000 B.C. Long before that these islands had been an Atlantean colony, but when Atlantis broke up they became a separate state, which passed through many vicissitudes as the ages rolled on. This part of the world has long been an area of vigorous volcanic activity, which has not even now entirely died out, as is witnessed by the tremendous eruption of Krakatau in 1883, which killed 35,000 people, and caused a 50-ft. tidal wave which travelled as far as Cape Horn, 7818 miles away, and even affected the level of the river Thames in London, besides throwing out so enormous a volume of dust that it rose to a height of two hundred miles and provided the whole world with phenomenally beautiful sunsets for two years thereafter.

In prehistoric times these islands were still part of the continent of Asia. At the present time the Java Sea is only 200 ft. deep, and the continuation of the channels cut by the rivers of Sumatra and Borneo may still be traced at the bottom of this comparatively shallow sheet of water. Even up to the year 915 A.D. the islands of Java and Sumatra were one, and it was an eruption of Krakatau in that year that broke them asunder and created the Straits of Sunda. Outbreaks on such a scale as this frequently devastated whole kingdoms, and had a serious influence upon the history of the country.

Black Magic from Atlantis

The colonists from Atlantis in the very early days had brought with them the dark and evil religion of their country, and as time rolled on, its hold upon the people became ever stronger and more pernicious. It was based entirely upon fear, as are all these gloomy faiths; they worshipped cruel and abominable deities, who required constant propitiation by human sacrifice, and they lived ever under the shadow of a ghastly tyranny from which no escape was possible.

They were ruled at the time to which I now refer by a dynasty of chiefs or kings, each of whom, like the Pharaoh of Egypt, was at the same time the high-priest of the religion; and among these priest-kings we find one who was specially earnest and fanatical in his awful faith. So far as can be seen in a brief examination, there seems no reason to doubt that his belief in these horrors was quite genuine; he had a kind of love for this fair land of Java, and he really thought that only by the perpetuation of his appalling scheme of daily blood sacrifices (which, however, were human only once a week, except on certain special festivals!) could his country be saved from utter destruction at the hands of the spiteful and bloodthirsty deities who were supposed to manifest their anger in frequent volcanic eruptions. Poor fellow, he was under the direct, inspiration of the Darker Powers, but of course he was quite unaware of that, and probably regarded himself as a patriot!

He was a man of great power and inflexible determination, and having worked out his terrible plan of sacrifice, he resolved to ensure as far as he could that it should be continued throughout the ages yet to come. To that end he worked a most elaborate system of magic, throwing by a tremendous and long-continued effort of his will a kind of spell upon the Island—laying it under a curse, as it were, that while his will held, the offering of the sacrifices should never fail. The result of his action may still be seen bothetherically and astrally, in the shape of a vast dark cloud hovering low over the Island, just not sufficiently material to be visible to ordinary physical eyesight, but very nearly so. And this malign cloud has the curious appearance of being “pegged down” at certain definite spots, so that it may not drift away.

These spots were of course specially magnetized by him for that purpose; they are nearly always coincident with the craters of the various volcanoes, presumably because these outlets are usually inhabited by a peculiar type of nature-spirits of marvelous tenacity, looking strangely like animated bronze images—a type which is specially susceptible to the kind of influence which he was using, and capable of retaining and reinforcing it for an indefinite period. Naturally also the Darker Powers whom, however unconsciously, he was serving took care to give his scheme such support as they could and thus it comes that this cloud is still in evidence even in the present day, though with far less than its ancient power.

An Aryan Invasion

The inhabitants of Java are a very mixed race—in fact, a conglomeration of races, but all having on the whole a preponderance of Atlantean blood. They were therefore in those earlier days under the jurisdiction of the Lord Chakshusha Manu; but He, being highly dissatisfied with the conditions then existing here, arranged with the Lord Vaivasvata Manu to send down a series of waves of Aryan immigration into the country in the hope of bringing about an improvement. The earliest of these waves with which my investigations have brought me into contact was somewhere about 1200 B.C., though I think that there had been previous efforts; but neither of them nor of this inflow does any definite tradition now remain among the royal archives.

These Hindu invaders seem to have come first as peaceful traders, settling on the coast and gradually forming themselves into small independent commercial States; but in process of time their power greatly increased, and they eventually became the dominant section of the mixed community, so that they were able to impose their laws and their ideals upon the earlier inhabitants. Their religion was Hinduism, though not perhaps of the purest type; but it was at least an enormous improvement upon what had preceded it here. One would have expected those of the older faith to welcome with enthusiasm any theory that would deliver them from its horrors; but as a matter of fact they do not seem to have taken kindly to the complicated ceremonies offered to them, and though under the new regime the foul and ghastly ancient rites were strictly forbidden, they were still extensively practised in secret. The new government suspected this, but feared to make a really determined effort to enforce its unpopular decrees; so the sacrifices were by no means eliminated, though they had to be offered surreptitiously.

Superstition always dies hard, and the more cruel and loathsome it is, the more tenaciously do its votaries cling to it. Hinduism remained the official religion of the country, but more and more as the centuries rolled on did the old devil-worship reassert itself, until its votaries scarcely troubled to conceal their nefarious practices, and the actual condition of the common people was very little better than before the invasion.

This being so, the Lord Vaivasvata decided to make another effort, so He inspired the celebrated Indian ruler Ring Ranishka of Northwest India to send down an expedition to Java in the year 78 A.D. The leader of this new enterprise is known in the tradition of the country as Aji Saka, or sometimes Sakāji, and his name is still reverenced by all the well-read Javanese.

He is credited by them with the final extirpation of cannibalism, the introduction (or perhaps rather the reassertion) of Hindu law and culture, of the caste system, of vegetarianism, of the Hindu epos and the Javanese script, which seems to be derived from the Deνanāgari.

He (since he was an orthodox Hindu), or more probably some of his officers, set up schools of Buddhism in both of its forms, the Hīnayāna and the Mahāyāna. The former seems to have prevailed for some time, but under the rule of the Shailendra Kings in the eighth century the latter school came into prominence, and eventually almost entirely superseded the Hīnayāna form. Buddhism was quickly and widely adopted in the Island, but its followers and those of the Brahmanical religion seem to have lived side by side in perfect amity and tolerance.

Magnetic Centres

Sakāji was well aware of the work which he had been sent to do. It is related of him in local tradition that in seven places in the country he buried certain strongly magnetized objects in order to rid Java of evil influences, endeavouring thus to counteract the “pinning down” process of the Atlantean priest-king. In the Javanese language these evil-destroying charms are called tumbal, and the fact of their existence is well known among the country folk. Though some of the feats attributed to him (such as the removal of certain mountains, etc.) partake rather of the character of the labours of Hercules, he is very far from being merely a legendary figure, and he has set his mark in many ways upon the country which he ruled so firmly. He may not have moved the mountains, but he gave them the Sanskrit names by which they are still universally known today.

A mountain in the Japara district, said to be the oldest and originally the highest elevation in the Island, was in earlier days identified with Μahāmeru but Sakāji gave it the name of Mauriapada—the footprint of Μaυrya. (1) In his time it had already beenextinct for ages, but secondary volcanic action was still in full swing. The Chinese annals of the period report especially a mud-fountain spouting heavenward to such a great height at Grobogan, south of the mountain, that sailors in the distant sea could see it and steer by it. Again, near Tuban (a word which means “welling up”) the same annals mention a well several miles from the coast with so rich an outpouring of fresh water that the sea-water for some distance was not at all salt, nor even brackish, but could be drunk with impunity.

(1) The dynasty of the Mauryas began in 322 B.C. after the death of Alexander. The Capital was Pātaliputra (now Patna). The Emperor Asoka was of Maurya dynasty.